6

Fatou is not able to make many visits to her native village, so she has scoured the Dakar side-walk markets for gifts to give to her numerous family members. There was also, of course, the wedding gift… or rather gifts, since Islam preaches that wives should be treated equally. “The beginning of a polygamous marriage is very delicate” Mady explains, “it can quickly become ‘complicated’ if jealousy arises”. In order to avoid any potential problems, Fatou has 2 identical dresses made. With no experience in African weddings, I asked Fatou to purchase my gifts as well; two sets of flower-print bed sheets.

7:20 a.m. We hail a taxi. Mor pouts as Fatou throws her bags in the trunk. I kiss him on the forehead, “we’ll be back soon, it’s just one week”. Fatou has already climbed in the taxi, giving the driver directions in a tone that would make one think that the President himself was waiting on us.

We are taken to a huge parking lot where one can catch a ride to all corners of Senegal, using transportation that range in quality and in price… Maurid buses, vans, taxis-brousses. We have opted for the 7-places, a station wagon that, as the name indicates, seats 7 people. The advantage is that passengers are grouped by destination, thereby cutting down on travel time… that is, if there aren’t any breakdowns on the road. After haggling over prices, we squeeze in to the back seat… and 6 hours later, we arrive in Koupentoum, the town on the main highway closest to Kissang.

Everyone warned me that it would be a lot hotter in the interior. But, I had NO IDEA it would be quite this hot… around 118 degrees (46° c), with scarce shade and zero breeze.

2 p.m. The sun shows us no mercy. Sleep deprived and already light-headed, I squint hoping to spot a haven from the heat… a cyber café, if I’m lucky. Apparently, we aren’t going to make the 7-mile trek through the wilderness towards her village until there is a truck full of people ready to go, which won’t happen until folks doing business in-town are done for the day. I can’t help but grumble to myself, “and why the heck did we have to leave so freakin’ early?” I do find a cyber-café but, there is only one computer and it doesn’t work. Shocking. I resign myself to following Fatou as she peruses the road-side stretch of stands, searching out last minute provisions… a flash light, a bar of soap, a small mirror and instant coffee.

6 p.m. My head pounding, nauseous, I pray for nightfall… yet 2 more hours go by before the sun sets, around the same time the truck finally cranks up for departure. Except, it doesn’t start. I have difficulty hiding my irritation while the other 20 odd people packed in and hanging on all sides remain calm as cucumbers. Eventually, the motor roars and a push-off gets us rolling.

8:30 p.m. I am jerked from my sleep, “Kissang! Ici! Kissang!” I can see nothing but swirls of flashlights. We are greeted by a high-pitched cacophony of voices. As I hop out the back of the truck, I am immediately surrounded by 30 screaming children, grabbing my arms, fighting to get a look at the toubab. Moments later, a shrieking order disperses them and like agile worker ants, they grab our stock of heavy bags, lift them over their heads and scurry towards the family compound.

Fatou’s brother, Ousmane welcomes us to his home, composed of a large dirt courtyard surrounded by 7 mud-straw huts and enclosed by a straw fence. Ousmane tells the children to bring us out a mattress. Exhausted and overwhelmed, I plop down, relieved to finally get some rest. 10 minutes later, a small troop calls for me to come. Ousmane says they have fetched water for my bath. Fatou follows behind. Mady has surely given her firm instructions to make sure I am closely watched over. “Liliane doesn’t know about brousse-life, she will need your help”. She accompanies me to the wash area, a small sectioned off square, attached to the outside of the living quarters. There is a bucket and a cup. Fatou explains with hand motions how it works. As I get undressed, she just stands there, apparently unconvinced that I can figure it out. She doesn’t budge until I tell her, “it’s o.k. Fatou, I understand the drill”.

Washed up, we take our seats back on the mattress and are brought dinner. We are served couscous made of mill, their staple means of nutrition, with a mafé sauce. Mady said I’d eat a lot of mafé while here, an inexpensive accompaniment to rice or couscous made of puréed peanuts, tomato paste and a few other condiments, depending on availability. In Kissang, a village where a total of maybe 4 or 5 people make wages, recipes contain the bare minimum.

After filling up on gritty peanut couscous, I lay my head down and instantly fall asleep. After an unknown period, I am awakened by a drum cadence outside the hut compound. The moon is full and has now risen high in the sky, illuminating the entire village. I peer outside the gate and see a gathering of 15 boisterous children forming a circle. 2 girls effortlessly create rhythmic beats with sticks and large empty jugs. The rest take turns making their way into the middle, showing off their limber, electric moves. Still delirious, and ill to my stomach, I hesitate to go out and join them. However, I am quickly spotted, brought towards the group and given a prime spot by the drummers. “Danser! Danser! Il faut danser!”. “Oh no, not tonight”. In my best Wolof (hoping someone will understand since the native language here is Mandingue) I explain, “dama sonn… dama feebar”. I am tired and I don’t feel well. The eldest girl, smiles, “graoul”, it’s o.k.

I was sorry to disappoint them. I knew it wasn’t haphazard that they had set up next to the Thiam home. I promised them I’d dance tomorrow. Soon after, I slipped away and went inside to rest my oh-so-weary head.

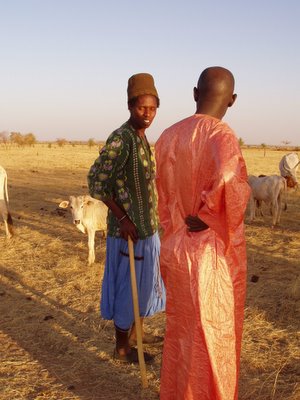

Groom and (second) Bride

Groom and (second) Bride

All in all the reunion was a success. It gave the volunteers a chance to meet the newcomers and discuss a bit their projects.

All in all the reunion was a success. It gave the volunteers a chance to meet the newcomers and discuss a bit their projects.