As soon as the sun rises, it is clear that today is a special day. The women spend the early morning working in triple time, carrying load after load of water jugs to fill the additional basins that have been brought over. The courtyard is full of women from the village, babies clenched to their backs, discussing the plan for feeding one hundred or so guests. They bring over extra cast iron cauldrons and wood for burning.

Fatou, a little distracted, quickly puts together a pot of hot water for my day’s ration of instant coffee. I pay close attention to the ladies, not understanding a word, but hoping to make a little sense of the massive orchestration. Once again, Fatou (honored guest because of the relative distance she traveled) affirms her status by starting the day in one of her prettiest and flashiest booboos. She seems a little more anxious than usual about getting me washed and ready for the day.

Not long after I’m cleaned up and dressed, we start to hear approaching drums. The bride is coming over from her village with a large entourage (probably half of her village). The women in the courtyard start to work a little faster. The bride’s parade is coming closer! Ousmane, though quite composed, wears an explosive grin. Kiné, his first wife, quietly retreats to her room.

Parade seen from afar, slowly making its way through the village.

Parade seen from afar, slowly making its way through the village.

Everyone seems focused on a task including all the young girls who are doing last minute brushings and wardrobe decisions. Syrah and Khadi must have changed in and out of different outfits at least 3 times.

When the sound of wildly beating drums could no longer be ignored, a stampede of women ran out from the courtyard to meet the crowd. The girls giggled, jumping around. The boys lined up, arm to arm, watching quietly. It was hard to see what was happening because of the many tall bodies bunched around the bride. I jumped up on a log and saw that she was concealed under a white sheet, standing behind a woman holding a rolled up bamboo mat that protrudes high above the crowd. The young woman thumps it mightily, following the cadence of the drums. Openings form in front of the bride. Villagers take turns dancing in the circle, stomping and raising their legs high, backs arched down parallel to the ground, arms straight out to the side.

When the sound of wildly beating drums could no longer be ignored, a stampede of women ran out from the courtyard to meet the crowd. The girls giggled, jumping around. The boys lined up, arm to arm, watching quietly. It was hard to see what was happening because of the many tall bodies bunched around the bride. I jumped up on a log and saw that she was concealed under a white sheet, standing behind a woman holding a rolled up bamboo mat that protrudes high above the crowd. The young woman thumps it mightily, following the cadence of the drums. Openings form in front of the bride. Villagers take turns dancing in the circle, stomping and raising their legs high, backs arched down parallel to the ground, arms straight out to the side.

The griots lead the cadence with their drums and short whistle blows.

Gender roles are so accentuated in Kissang that even as children, boys and girls play separately.

As the guests streamed in the courtyard, so did the gifts. Women carried iron pots, clay jars, mats, cups and bowls, fabric to adorn the walls, blankets. The men carried in a large chest and armoire. I hadn’t seen but a couple pieces of furniture in the whole village. Was his second wife’s family better situated? It's hard to know since often times, wedding gifts are bought with the dowry agreed upon in marriage negotiations. The Senegalese tell me that most often, a man’s first wife is chosen for him amongst the parents, even as early as birth, making negotiations a smoother affair. The second wife is the man's choice. The man pursues a woman based on personal interest and attraction which necessarily tips the scale in favor of the bride’s party when deciding how large a dowry he’ll have to pay.

Ousmane and his second wife, Ker, were actually married over a year ago, a quick formality done in the mosque with only the parents present. Today’s ceremony marks a more important event. She will finally join her husband. Why the wait? Ousmane first had to get the house ready (build the additional mud hut) and save enough money to provide for his new wife and young child (apparently Ousmane was allowed conjugal visits). And of course, he also had to get the money and food stock together for today’s grand affair. I’d calculate it at about a little over a year’s worth of (Senegalese) wages.

The bamboo mats are rolled out under the covered porch. Ousmane and his bride sit next to one another. Women and children fill in around them. The men cross over to the other end of the courtyard to find a place under the second covered porch. Then, after a series of symbolic offerings and benedictions, the young girl’s white shroud is pulled back. The singing and clapping continue for hours while different villagers take turns sitting in front of the new couple, offering them sage advice. Always followed by a trail of “amin, amin, amin…”

Meanwhile, groups of women pour in and out of Kiné's, the first wife's, room. The older women sit in front of her, giving her firm instruction on how she should treat her co-spouse. “Treat her as she is your own daughter, teaching her how to take good care of the home and the family!” I had peaked in on Kiné throughout the day. She was solidly stoic with heavy eyes. She remained aloof, even whilst the women yelled proverbs of domestic living. The women, packed tightly into the mud hut, after each lecture would break out in to high pitched singing and chaotic dancing, clanging large spoons on metal bowls. The loud din spilling out of the case made one think the women were trying to chase away Kiné’s sorrow with noise.

Eventually, the courtyard grew quiet for the marabout’s sermon. I learned later, when I asked the school teacher, that he spoke of the different roles between husbands and wives. He said this was the first ceremony he had gone to where the iman also stressed the importance of a man’s obligation to his wife (or wives).

After the speaker finished, the big moment arrived. The new wife would be taken into the first wife’s chamber. It was a moment I didn’t want to miss. Though I literally could not even fit my foot in the room, I did manage to sneak a look in from the hut's back entrance. They did the traditional side-to-side hug to the shrill of more proverbs, singing, and clamber of metal spoons and bowls. After a few songs, the bride and her entourage stream out of the room. Tucked behind the curtain, I wait. When the last woman in the hut steps out, a large stream of tears rolled down Kiné’s cheeks. It triggered such a strong emotion within me that my eyes quickly became a blur. This moment did not last more than a minute. Kiné knew the women would soon be back. She wiped her eyes and laid out a beautiful blue booboo, made special for the occasion.

Ousmane with his young new bride (Ker) on the left and first wife (Kiné) on the right.

Ousmane’s wide grin had not once left him since I had first spotted him in early morning. He was exceedingly proud of the great many guests that had shown up and of his beautiful brides. Ousmane introduced me to every single family member and to many friends. I took a great number of photos upon his request.

I asked him a lot of questions during the day since he was one of the few who spoke a little French. At one point, while we were sitting in his hut, he told me that I'm pretty and nice and asked if we could get to know one another better. I try to keep my sarcasm to a polite level. “Oh Ousmane" I say, "you already have two beautiful wives, that should be enough!”. “But,” he says, “there is always room for a third." I blink three times, too stunned to make an expression. He is not hitting on me on his wedding day, is he? Ousmane bursts out in laughter. Oh o.k., he must be joking.

No, he wasn’t. Later, he approaches me again and says, “Liliane, if you change your mind, let me know. At least stay in contact while you are still in Dakar. Give me your number and I’ll call you.” Senegalese men have a way of just telling you what to do. Very unnerving for a Western girl. By this time, I was ready to march out to that water tower where I could be alone and collect myself. I was eager to call my sweet heart since I wanted reminding that women from my neck of the woods had achieved emancipation and that polygamy, in my culture, is a pipe dream!

On my way back, I ran into the donkurons, the ceremonial dancers. There were three, covered in leaves and branches, their faces hidden. Everyone was particularly excited about the donkurons. I had heard talk of them weeks before the wedding from Mady and Fatou. Approaching the compound, the drums started again and a huge crowd formed. The dancing was like a competition. Each one trying to outdo the other. It seemed the victor was he who created the most movement. The speed at which they stomped and jumped around while staying in rhythm was incredible.

As the sun inched lower on the horizon, the freshly slaughtered mouton was getting cleaned and broken down by the women’s cooking squad. Most of the roughly cut up animal was thrown in the stew: head, innards, and parts unidentifiable. I stood around for a moment, as I did for most meals, but quickly realized I risked ruining my appetite for tonight’s feast. So instead, I followed cousin Khadi as she mingled through the crowd. Khadi is animated and energetic. I needn’t understand Mandingue to get the gist of what she was saying.

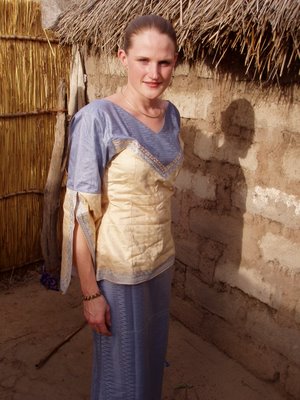

After my evening rinse, I put on my one and only booboo. I had saved it for the culmination point of the marriage cermony. Several guests complimented my Senegalese look. Khadi, on the other hand, surprised me with a very Western looking get up; tight black pants and a sleeveless black and white top with high heeled sandals. She looked like she was ready for the big city clubs! The two brides washed up and came out, each in a beautifully adorned booboo.

At 16 years of age, I estimate Ker is about half as young as her co-spouse Kiné who already has 4 kids.

Meanwhile, young Syrah was working doggedly. Being Ousmane’s eldest girl, she was always the person who got called on if someone needed something. She was up until 4am the night before brewing pot after pot of the traditional tea. Today she was up at 6 am filling water basins, running after toddlers, serving meals and sweeping floors. She was also in charge of watching after me. She spoke only a little French however the little bit she did speak was helpful. She served as a translator when I was amongst the women which was most of the time. Syrah’s in 6th grade and currently living in the nearest village with an upper level school. She came home special for the wedding. I asked her how she felt about getting a second mother. She thought for a moment, laughed lightly, shrugged her shoulders and said she was o.k. with it. Syrah works very hard and never complains. She has the smile of a genuinely happy heart.

The bride and the women of her entourage were not spared of work either. Even in their loveliest attire, they all shared the work of preparing for the night's feast.

Dinner was served late. I followed Fatou into Kiné's hut to share in the women’s platter. I was used to meat chunks in the meal, but this looked to be only connective tissues. I imagine the meat went to the male guests. The woman didn’t seem to mind, practically fighting over the hard chewy pieces.

Not long after bellies were filled, the crackly speakers spewed out the same muffled tracks as the night before. Mbalax! They never get tired of it. Khadi runs out to dance, dragging me along. Certain my mbalar dance moves have not improved overnight, I stick around for the beginning of the song which is slower and then sneak off when it crescendos into chaotic beats. Khadi persists however. Everytime she spotted me, she’d grab my hand and take me back out to the fog of dust kicked up the big group of dancers.

Eventually, I had had it. Exhausted by the day’s heat and the emotional boulversement, I was ready to once again find a spot on the mat outside nestled among a half dozen sleeping babies. Even with the loud ruckus, I slept soundly up until just before dawn when I am summoned to come to Kiné’s room. I squeeze in to a bed already filled with 5 sleeping bodies and drift back to sleep.